NIH study in mice explains how brain can turn pain signals up or down

For Immediate Release:

Tuesday, October 15, 2019

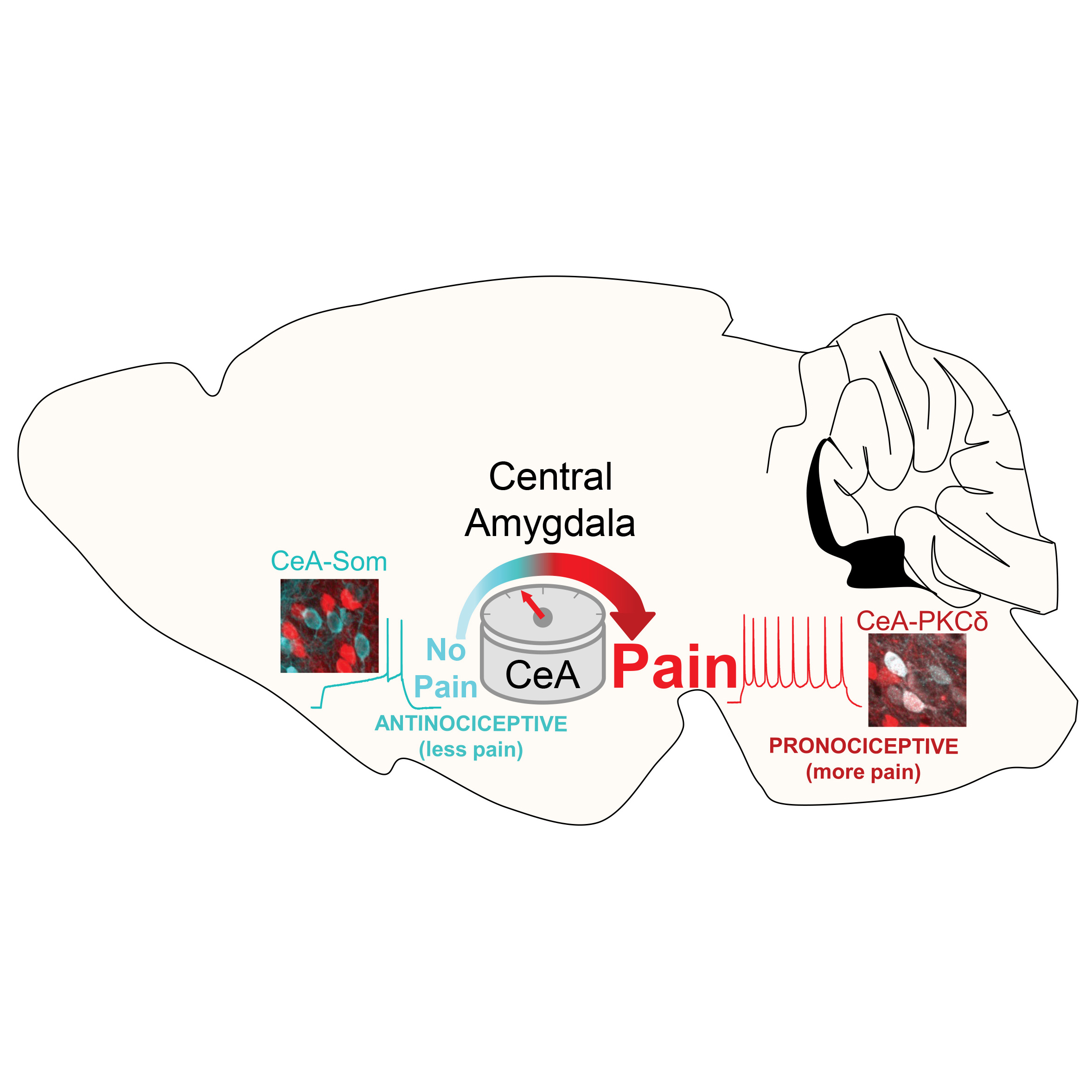

A new study in mice uncovered a previously unknown role that the central amygdala can play in upgrading or downgrading pain signals in the brain’s circuitry. The study, published in Cell Reports, was conducted by researchers at the Division of Intramural Research at the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), part of the National Institutes of Health.

“We know that pain is not static and that it can be modulated by several factors. Early research showed that the central amygdala, long known for its role in processing fear, can dial up pain signals. Yet, other studies have pointed to the central amygdala’s role in suppressing pain, or prompting an analgesic response,” said Yarimar Carrasquillo, Ph.D., senior author of the study and lead scientist for the Behavioral Neurocircuitry and Cellular Plasticity Section in the NCCIH Intramural Division. “This study unravels what seemed to be a contradiction in early research and reveals a previously hidden ‘switch’ in the central amygdala that can turn up or turn down pain signals.”

The “switch” acts more like a “pain rheostat,” similar to a home thermostat that modulates temperature—the pain rheostat reacts to pain signals to modulate pain sensations. In the mice, researchers found that activity in neurons that express protein kinase C-delta (CeA-PKCδ) turned up the pain rheostat and demonstrated an increase in pain-related responses. Conversely, researchers found that activity in neurons that express somatostatin (CeA-Som) turned down the pain rheostat, inhibiting nociception or the chain of activity in the nerves required to communicate pain.

During the experiments, researchers were able to take advantage of molecular genetic approaches that allow them to fluorescently label and manipulate the activity of these two central amygdala cell types. They found that when they blocked CeA-PKCδ neurons, pain activity decreased. When researchers activated CeA-Som neurons, they observed a marked analgesic response in mice.

“This new understanding of the amygdala’s dual role, and the pathways that can promote the perception of pain or prompt an analgesic response, is critical to understanding how pain manifests,” said Helene M. Langevin, M.D., NCCIH director. “It also provides new clues for researchers to pursue in learning how we might manage pain by modulating what’s happening in the brain.”

While pain perception is essential for survival, it can be amplified or suppressed by factors like expectations, past experiences, and context. The research team led by Dr. Carrasquillo conducts basic science research into anatomical, molecular, and cellular mechanisms to better understand the mechanisms of pain modulation in the brain.

The study is part of NCCIH’s broad range of intramural and extramural efforts to address the issue of pain and chronic pain in the United States, including NCCIH’s role in the NIH-wide HEAL (Helping to End Addiction Long-termSM) Initiative and the NIH-DoD-VA Pain Management Collaboratory. Approximately 40% of NCCIH’s overall budget focuses on pain.

Pain is the most common reason patients in the U.S. seek medical care and one of the most common reasons people turn to complementary health approaches. The 2012 National Health Interview Survey showed that about 11% of U.S. adults have pain every day and more than 17% have severe levels of pain.

This press release describes a basic research finding. Basic research increases our understanding of human behavior and biology, which is foundational to advancing new and better ways to prevent, diagnose, and treat disease. Science is an unpredictable and incremental process—each research advance builds on past discoveries, often in unexpected ways. Most clinical advances would not be possible without the knowledge of fundamental basic research.

###

About the National Center for Complementary and Integrative

Health (NCCIH):

NCCIH’s mission is to define, through rigorous scientific

investigation, the usefulness and safety of complementary and

integrative health approaches and their roles in improving

health and health care. For additional information, call

NCCIH’s Clearinghouse toll free at 1-888-644-6226. Follow us

on Twitter, Facebook ,

and YouTube.

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH): NIH, the nation’s medical research agency, includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit www.nih.gov.