Children and the Use of Complementary Health Approaches

What’s the Bottom Line?

How much do we know about complementary health approaches for children?

We know a lot about the usage rates of complementary health approaches for children but little about their effects and safety.1

What do we know about the effectiveness of complementary health approaches for children?

Studies have looked at many complementary health approaches for children with different conditions, but the evidence generally isn’t strong enough to show what works and what doesn’t.

What do we know about the safety of complementary health approaches for children?

Many complementary approaches haven’t been tested for safety in children.

1 In the past, children were often excluded from research studies due to special protections, and findings from studies of adults were applied to children. Today, the National Institutes of Health requires that children be included in all studies, unless there are scientific and ethical reasons not to.

Patterns in the Use of Complementary Health Approaches for Children

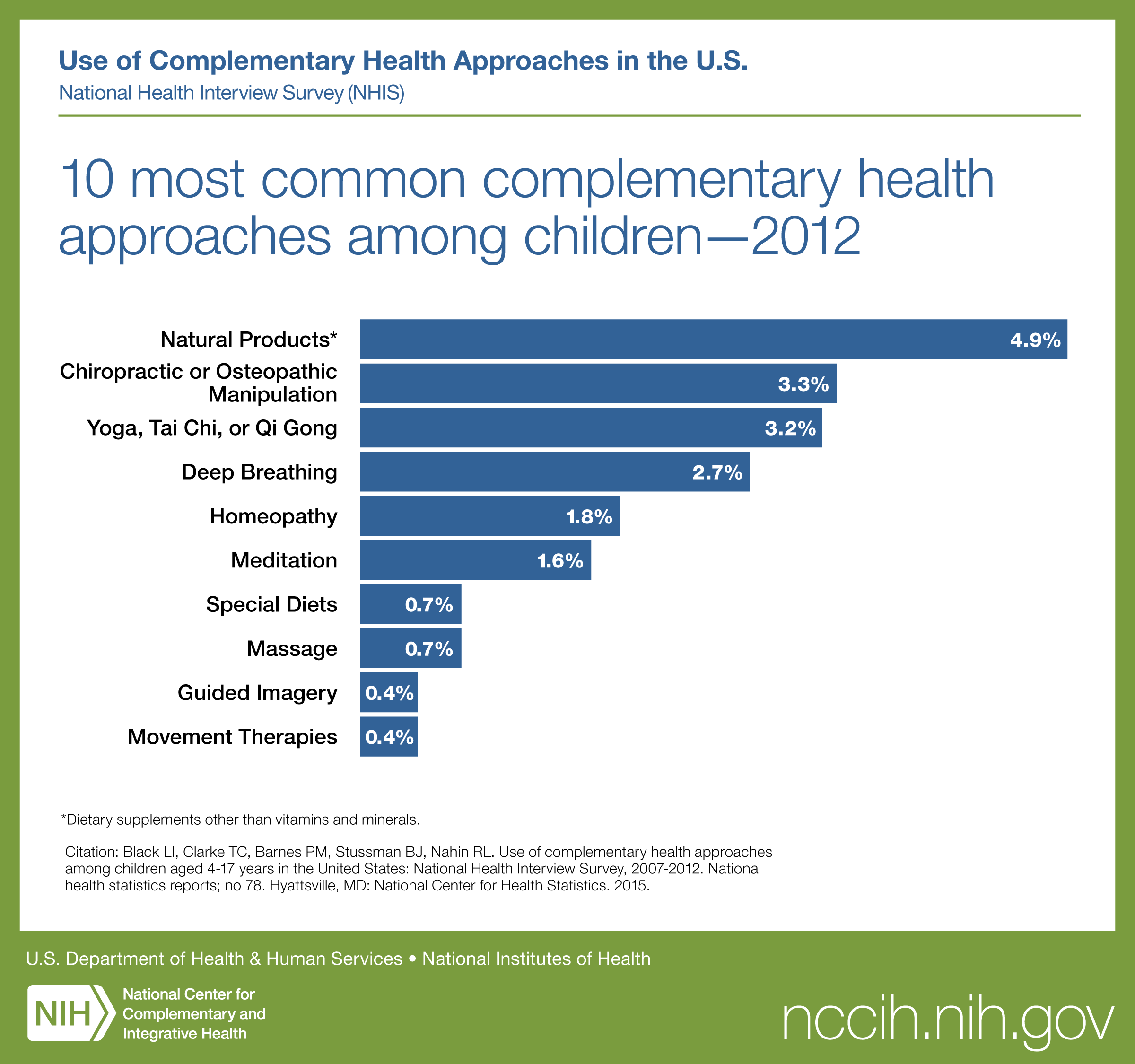

The 2012 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) included a comprehensive survey on the use of complementary health approaches by almost 45,000 Americans, including more than 10,000 children aged 4 to 17. The survey found that 11.6 percent of the children had used or been given some form of complementary health product or practice, such as yoga or dietary supplements, during the past year. Data from the 2017 NHIS found that from 2012 to 2017 the use of yoga and meditation in the past 12 months significantly increased among U.S. children (aged 4 to 17 years). The percentage of children using yoga more than doubled and the percentage of children meditating showed an almost tenfold increase.

The most frequently used approaches for children were natural products2 (fish oil, melatonin, and probiotics), and chiropractic or osteopathic manipulation.

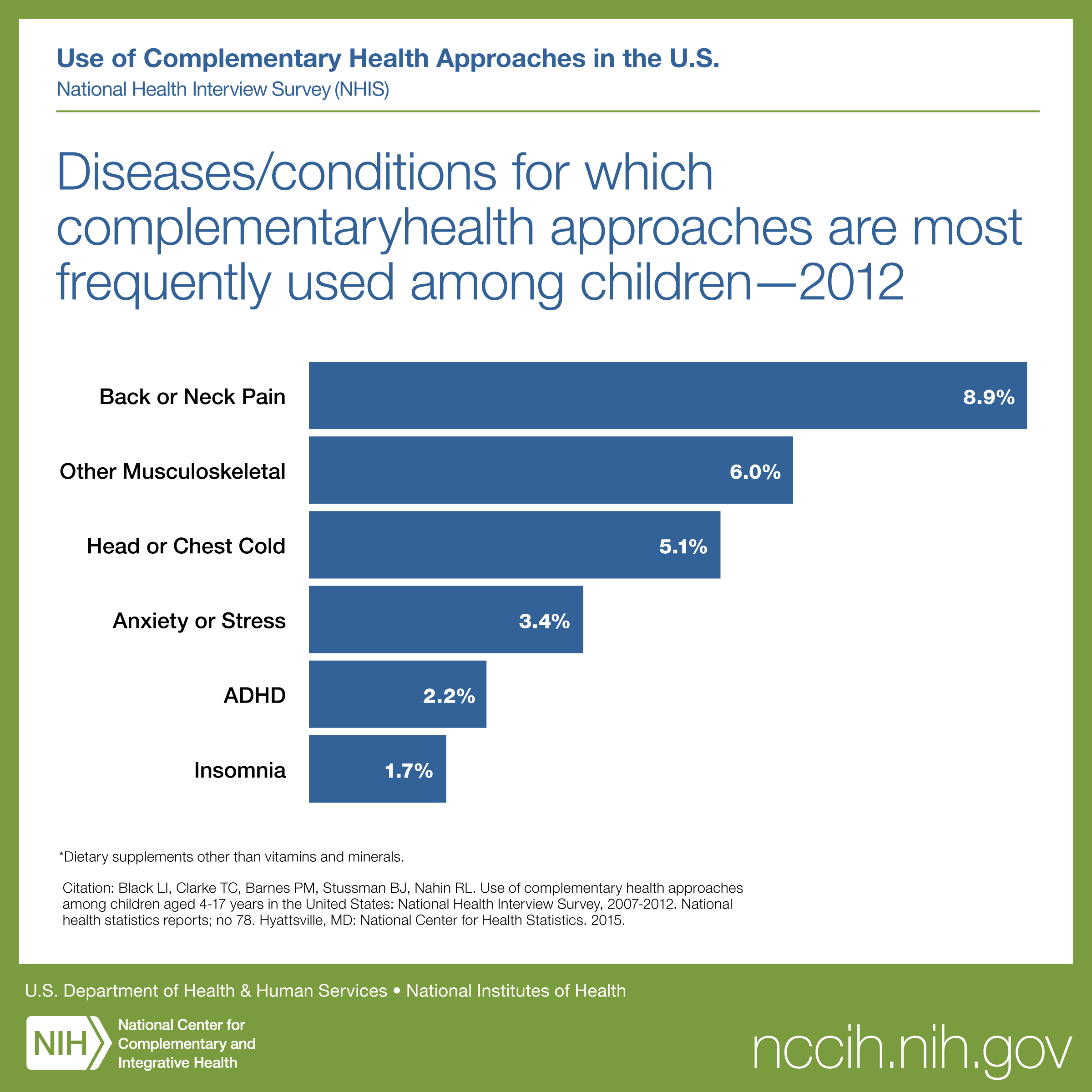

For children, complementary health approaches were most often used for back or neck pain, other musculoskeletal conditions, head or chest colds, anxiety or stress, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or attention-deficit disorder (ADD), and insomnia or trouble sleeping.

For more information from the NHIS study on children’s use of complementary health approaches, visit the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health’s (NCCIH) NHIS Statistics pages at nccih.nih.gov/research/statistics/NHIS/2012.

2 This does not include vitamins and minerals.

Other studies show that children in the United States who use or are given complementary health approaches vary in age and health status. For example:

- About 10 percent of infants are given teas or botanical supplements, usually for fussiness or stomach problems.

- About 40 percent of children aged 2 to 8 are given dietary supplements containing vitamins or minerals. However, that age group generally eats a nutritionally adequate diet.

- Teens are particularly likely to use products that claim to improve sports performance, increase energy levels, or promote weight loss.

- Children with chronic medical conditions, including anxiety, musculoskeletal conditions, and recurrent headaches, are more likely than other children to use complementary health approaches, usually along with conventional care.

What the Science Says About the Safety and Side Effects of Complementary Health Approaches for Children

- Dietary supplements result in about 23,000 emergency room visits every year. Many of the patients are young adults who come to the emergency room with heart problems from taking weight-loss or energy products. One-fifth of the visits are children; most of whom took a vitamin or mineral when unsupervised. (Child-resistant packaging isn’t required for dietary supplements.)

- Some dietary supplements contain contaminants, including drugs, chemicals, or metals.

- Children’s small size, developing organs, and immature immune system make them more vulnerable than adults to having allergic or other adverse reactions to dietary supplements.

- Some products may worsen conditions. For example, echinacea is a type of ragweed so people sensitive to ragweed may also react to echinacea.

- Do not rely on asthma products sold over-the-counter and labeled as homeopathic, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warns. Homeopathic remedies and dietary supplements are not evaluated by the FDA for safety or effectiveness. To learn more, visit NCCIH’s webpage on homeopathy.

- Biofeedback, guided imagery, hypnosis, mindfulness, and yoga are some of the complementary health approaches that have the best evidence of being effective for children for various symptoms (such as anxiety and stress) and are low-risk. However, spinal manipulation, a common complementary approach, is associated with rare but serious complications.

More to Consider

- Make sure that your child has received an accurate diagnosis from a licensed health care provider.

- Educate yourself about the potential risks and benefits of complementary health approaches.

- Ask your child’s health care provider about the effectiveness and possible risks of approaches you’re considering or already using for your child.

- Remind your teenagers to talk to their health care providers about any complementary approaches they may use.

- Do not replace or delay conventional care or prescribed medications with any health product or practice that hasn’t been proven safe and effective.

- If a health care provider suggests a complementary approach, do not increase the dose or duration of the treatment beyond what is recommended (more isn’t necessarily better).

- If you have any concerns about the effects of a complementary approach, contact your child’s health care provider.

- As with all medications and other potentially harmful products, store dietary supplements out of the sight and reach of children.

- The NCCIH website offers safety tips on dietary supplements for children and teens.

- Tell all your child’s health care providers about any complementary or integrative health approaches your child uses. Give them a full picture of what you do to manage your child’s health. This will help ensure coordinated and safe care.

Selecting a Complementary Health Practitioner

If you’re looking for a complementary health practitioner for your child, be as careful and thorough in your search as you are when looking for conventional care. Be sure to ask about the practitioner’s:

- Experience in coordinating care with conventional health care providers.

- Experience in delivering care to children.

- Education, training, and license. For more information on credentialing, see the NCCIH website.

NCCIH offers more information on how to find a complementary health practitioner on its website.

For More Information

NCCIH Clearinghouse

The NCCIH Clearinghouse provides information on NCCIH and complementary and integrative health approaches, including publications and searches of Federal databases of scientific and medical literature. The Clearinghouse does not provide medical advice, treatment recommendations, or referrals to practitioners.

Toll-free in the U.S.: 1-888-644-6226

Telecommunications relay service (TRS): 7-1-1

Website: https://www.nccih.nih.gov

Email: info@nccih.nih.gov (link sends email)

Know the Science

NCCIH and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) provide tools to help you understand the basics and terminology of scientific research so you can make well-informed decisions about your health. Know the Science features a variety of materials, including interactive modules, quizzes, and videos, as well as links to informative content from Federal resources designed to help consumers make sense of health information.

Explaining How Research Works (NIH)

Know the Science: How To Make Sense of a Scientific Journal Article

PubMed®

A service of the National Library of Medicine, PubMed® contains publication information and (in most cases) brief summaries of articles from scientific and medical journals. For guidance from NCCIH on using PubMed, see How To Find Information About Complementary Health Practices on PubMed.

Website: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews is a collection of evidence-based reviews produced by the Cochrane Library, an international nonprofit organization. The reviews summarize the results of clinical trials on health care interventions. Summaries are free; full-text reviews are by subscription only.

Website: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/

Office of Dietary Supplements (ODS), National Institutes of Health (NIH)

ODS seeks to strengthen knowledge and understanding of dietary supplements by evaluating scientific information, supporting research, sharing research results, and educating the public. Its resources include publications (such as Dietary Supplements: What You Need To Know) and fact sheets on a variety of specific supplement ingredients and products (such as vitamin D and multivitamin/mineral supplements).

Website: https://ods.od.nih.gov

Email: ods@nih.gov (link sends email)

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

The FDA oversees the safety of many products, such as foods, medicines, dietary supplements, medical devices, and cosmetics. See its webpage on Dietary Supplements.

Toll-free in the U.S.: 1-888-463-6332

Website: https://www.fda.gov/

Federal Trade Commission (FTC)

The FTC is the Federal agency charged with protecting the public against unfair and deceptive business practices. A key area of its work is the regulation of advertising (except for prescription drugs and medical devices).

Toll-free in the U.S.: 1-877-382-4357

Website: https://www.ftc.gov

NIH Clinical Research Trials and You

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) has created a website, NIH Clinical Research Trials and You, to help people learn about clinical trials, why they matter, and how to participate. The site includes questions and answers about clinical trials, guidance on how to find clinical trials through ClinicalTrials.gov and other resources, and stories about the personal experiences of clinical trial participants. Clinical trials are necessary to find better ways to prevent, diagnose, and treat diseases.

Website: https://www.nih.gov/health-information/nih-clinical-research-trials-you

Key References

- Bailey RL, Fulgoni VL, Keast DR, et al. Do dietary supplements improve micronutrient sufficiency in children and adolescents? Journal of Pediatrics. 2012;161(5):837–842.

- Black LI, Barnes PM, Clarke TC, Stussman BJ, Nahin RL. Use of yoga, meditation, and chiropractors among U.S. children aged 4–17 years. NCHS Data Brief, no 324. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2018.

- Black LI, Clarke TC, Barnes PM, Stussman BJ, Nahin RL. Use of complementary health approaches among children aged 4–17 years in the United States: National Health Interview Survey, 2007–2012. National health statistics reports; no 78. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2015.

- Clarke TC, Barnes PM, Black LI, Stussman BJ, Nahin RL. Use of yoga, meditation, and chiropractors among U.S. adults aged 18 and over. NCHS Data Brief, no 325. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2018.

- Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, Barnes PM, Nahin RL. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002–2012. National health statistics reports; no 79. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2015.

- Geller AI, Shehab N, Weidle NJ, et al. Emergency department visits for adverse events related to dietary supplements. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;373(16):1531–1540.

- George M, Topaz M. A systematic review of complementary and alternative medicine for asthma self-management. Nursing Clinics of North America. 2013;48(1):53–149.

- Humphreys BK. Possible adverse events in children treated by manual therapy: a review. Chiropractic & Osteopathy. 2010;18:12.

- Kemper KJ, Vohra S, Walls R. American Academy of Pediatrics. The use of complementary and alternative medicine in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2008;122(6):1374–1386.

- McClafferty H. Complementary, holistic, and integrative medicine: mind-body medicine. Pediatrics in Review. 2011;32(5):201–203.

- Meyer S, Gortner L, Larsen A, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine in paediatrics: a systematic overview/synthesis of Cochrane Collaboration reviews. Swiss Medical Weekly. 2013;143:w13794.

- Snyder J, Brown P. Complementary and alternative medicine in children: an analysis of the recent literature. Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 2012;24(4):539–546.

- Todd AJ, Carroll MT, Robinson A, et al. Adverse events due to chiropractic and other manual therapies for infants and children: a review of the literature. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 2015;38(9):699–712..

- Vohra S, Johnston BC, Cramer K, et al. Adverse events associated with pediatric spinal manipulation: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):e275–e283.

- Zhang Y, Fein EB, Fein SB. Feeding of dietary botanical supplements and teas to infants in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011;127(6):1060–1066.

All Other References

- Cramer H, Posadzki P, Dobos G, et al. Yoga for asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 2014;112(6):503–510.

- Ethical Conduct of Clinical Research Involving Children. In: Field MJ, Behrman RE, eds. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Clinical Research Involving Children. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2004. Accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK25542/ on March 25, 2016.

- Krisanaprakornkit T, Ngamjarus C, Witoonchart C, et al. Meditation therapies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010;(6):CD006507. Accessed at www.cochranelibrary.com on March 25, 2016.

- Levi JR, Brody RM, McKee-Cole K, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine for pediatric otitis media. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 2013;77(6):926–931.

- Li S, Yu B, Zhou D, et al. Acupuncture for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011;(4):CD007839. Accessed at www.cochranelibrary.com on March 25, 2016.

- Lim A, Cranswick N, South M. Adverse events associated with the use of complementary and alternative medicine in children. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2011;96(3):297–300.

- Marchisio P, Bianchini S, Galeone C, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in children with recurrent acute otitis media in Italy. International Journal of Immunopathology and Pharmacology. 2011;24(2):441–449.

- NIH inclusion of children as participants in research involving human subjects. National Institutes of Health. Office of Extramural Research Web site. Accessed at grants.nih.gov/grants/funding/children/children.htm on March 25, 2016.

- Sánchez-Barceló EJ, Mediavilla MD, Reiter RJ. Clinical uses of melatonin in pediatrics. International Journal of Pediatrics. 2011;2011:892624.

- Saper RB, Phillips RS, Sehgal A, et al. Lead, mercury, and arsenic in US- and Indian-manufactured Ayurvedic medicines sold via the Internet. JAMA. 2008;300(8):915–923.

- Schetzek S, Heinen F, Kruse S, et al. Headache in children: update on complementary treatments. Neuropediatrics. 2013;44(1):25–33.

- Woolf AD, Gardiner P. Use of complementary and alternative therapies in children. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2010;87(2):155–157.

This publication is not copyrighted and is in the public domain. Duplication is encouraged.

NCCIH has provided this material for your information. It is not intended to substitute for the medical expertise and advice of your health care provider(s). We encourage you to discuss any decisions about treatment or care with your health care provider. The mention of any product, service, or therapy is not an endorsement by NCCIH.